As with my previous Earthwatch Fellowship, this trip embodied the idea of Citizen Science: Anyone, with the assistance of a professional scientist, can contribute to the scientific research process in meaningful ways. My job, as a Senior Fellow, was to lead workshops for the other teacher fellows that facilitate and foster dialogue on ways to incorporate our Earthwatch experience in the classroom.

Our lead researcher, Dr. Lee Dyer, has worked with Earthwatch for close to 25 years, leading over 5,000 citizen scientists on trips all over the world. One of the coolest parts of Earthwatch, however, are the varied excursions they offer for different groups of people:

Student Trips: The Earthwatch Ignite Program is designed for aspiring scientists in the 10th and 11th grades to participate on a fully-funded expedition. If you know somebody who would be interested, here's a link to the application.

Corporate Partnerships: One of the most fascinating aspects of Earthwatch's work are their corporate partnerships. C-Level Suite executives from fortune 500 companies, including Credit Suisse and HSBC, participate on an Earthwatch expedition as part of their corporate social responsibility initiative. Dr. Dyer said that many executives start their trip either climate deniers or apathetic to climate change, and leave with a sense of passion and vigor in fighting global warming.

Retail Trips: For folks who aren't teachers, students, or corporate executives, it is possible to pay your own way on an Earthwatch expedition of your choosing.

I, of course, participated on the Teach Earth Fellowship for educators. For eight days, nine teacher fellows, myself, and three researchers traveled through the breathtaking landscape of southern Arizona in search of Lepidoptera, the scientific name for caterpillars.

Our lead researcher, Dr. Lee Dyer, has worked with Earthwatch for close to 25 years, leading over 5,000 citizen scientists on trips all over the world. One of the coolest parts of Earthwatch, however, are the varied excursions they offer for different groups of people:

Student Trips: The Earthwatch Ignite Program is designed for aspiring scientists in the 10th and 11th grades to participate on a fully-funded expedition. If you know somebody who would be interested, here's a link to the application.

Corporate Partnerships: One of the most fascinating aspects of Earthwatch's work are their corporate partnerships. C-Level Suite executives from fortune 500 companies, including Credit Suisse and HSBC, participate on an Earthwatch expedition as part of their corporate social responsibility initiative. Dr. Dyer said that many executives start their trip either climate deniers or apathetic to climate change, and leave with a sense of passion and vigor in fighting global warming.

Retail Trips: For folks who aren't teachers, students, or corporate executives, it is possible to pay your own way on an Earthwatch expedition of your choosing.

I, of course, participated on the Teach Earth Fellowship for educators. For eight days, nine teacher fellows, myself, and three researchers traveled through the breathtaking landscape of southern Arizona in search of Lepidoptera, the scientific name for caterpillars.

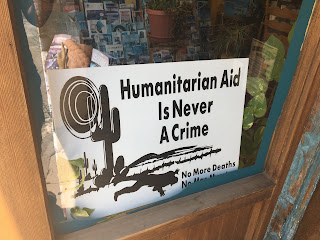

We started our journey at the Southwest Research Station just outside of Portal, Arizona. After 3 days, we then moved west, passing through Bisbee, and finally finished in Arivaca, Arizona. At one point during our expedition, we were so close to the Mexican border that many of us received text messages from our cellphone carriers offering to buy international data plans!

A Brief Description of the Research (Courtesy of Earthwatch):

On this project, we examine the factors that affect interactions among plants, caterpillars, and their natural enemies. This is an important area of study for both agricultural and basic ecology. This three-tiered study system allows for insights into “tri-trophic” interactions— in other words, it examines the relationships among three distinct levels of the food web. We conducted caterpillar research in the deserts and mountains around the Southwest Research Station in the Chiricahua Mountains and the nearby Santa Rita Experimental Range in the Coronado National Forest. Other Earthwatch teams conduct work throughout the year in forests and mountains in Nevada and California; a rainforest at La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica; a cloud forest at Yanayacu Biological Station in Ecuador; and in urban areas, swamps, and bottomland hardwood forests around New Orleans, Louisiana.

The natural enemies of caterpillars that the project studies are called “parasitoids.” They include many species of wasps and flies that kill caterpillars by depositing their eggs on them. This ensures that the parasitoids’ offspring will have both a safe environment in which to grow (inside the caterpillar) and a good supply of food (caterpillar tissue). We are rearing caterpillars of over 300 species and recording the mortality caused by the parasitoids. In addition, we isolate specific chemical compounds from some species of caterpillars and food plants to examine them as potential defenses against parasitoids.

By comparing the results from different sites, we can test hypotheses about the effects of climate on interactions between caterpillars and parasitoids. Our study also collects essential natural history information about plants, caterpillars, and parasitoids. Based on our data, we are developing models to predict which parasitoids might be used to control specific insect pests of human crops, which will benefit farmers who are attempting to control pests without using pesticides. Some of the species that we study (such as army worms and owl butterfly caterpillars) are agricultural pests; others (such as some rare day flying moths) are threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation. The caterpillars we worked with are fascinating: they come in a spectacular diversity of shapes, colors, and forms that function to defend them against their enemies. Many of the species found by this project will be new to science.

The Research Process

In order to carry out this important research, thousands of caterpillar specimens must be collected, reared, and studied. Our team successfully completed 16 plots throughout southern Arizona. The process of setting up a plot, collecting specimens, and rearing caterpillars is quite involved:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Beat sticks and nets, pictured above, are used to retrieve the caterpillars. We literally "beat" the branches until the caterpillars fell off!

|